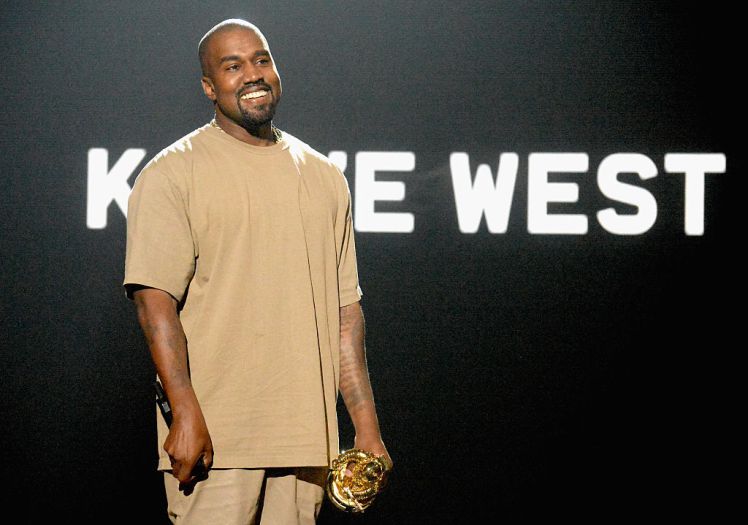

So Kanye’s back on Twitter and, surprise, surprise, he’s once again doing his damnedest to prove how much of a free thinking innovator he is. This time, though, he’s going about it in a particularly puzzling manner – by actively endorsing conservative talking points and reiterating his love for President Trump.

Now, Ye’s never been one to shy away from politics, whether it be by incorporating relevant social commentary into the lyrics of his songs, or by openly accusing Bush of not caring about black people on national television as the events around hurricane Katrina made it evident that the State’s response to the tragedy had been less than adequate. Bearing this in mind, it’s not surprising that Kanye would continue to voice his opinions on matters of political or social relevance, especially considering the fact that his new album is coming out in a little over a month; controversy is the most valuable form of marketing currency for those who can afford to sacrifice some of their core audience in the name of achieving even further popularity with the masses.

What is surprising, though, is how Kanye seems to have undergone a complete metamorphosis and transformed into a new beast entirely; whereas his previous records featured songs like New Slaves wherein he lamented the systemic pitfalls placed squarely in the path of every poor black person in the United States, Kanye’s current stance seems to be more in line with the hard-right’s view on issues of race and poverty in the black community; slavery, according to West, is a trend, a fashionable excuse for those who haven’t managed to succeed in life and are much too weak to face the reality of their own ineptitude, constructing instead a web of historic and political circumstances that kept them at the bottom.

These tweets come just hours after Yeezy’s endorsement of Candace Owens, a TPUSA collaborator and black conservative thinker who recently delivered a speech on the irrelevance and even downright toxicity of the Black Lives Matter movement as TPUSA founder Charlie Kirk looked on and smiled at Owens’ repeated jabs at what she described as a victim mentality that is widespread among black communities around the US and also acts as the primary driver behind poverty in said communities.

Owens’ talking points are hardly compelling or original – her views basically amount to a race-centered reframing of the so called ‘bootstrap’ mentality that initially started out as a joke about trickle down economics during the Reagan years but turned into a genuine argument that conservatives employ when discussing issues of generational poverty, unemployment, and crime; to engage with purveyors of bootstrapping, one must first understand the a priori reasoning that lies at its heart – a Randian conception of the individual as a sort of pseudo-economic unit whose one and only true pursuit is that of its own rational self-interest, ergo every failure to achieve said self-interest is to be analyzed as a failure of the individual rather than as a consequence of the mechanism by which some overarching apparatus of repression operates (this only applies within the frame of the only economic system that conservatives and libertarians truly believe in, laissez-faire capitalism). And, as most right-wingers regard the US as a bastion of free trade, free enterprise and all other forms of freedom, it stands to reason that the only thing truly holding African-Americans back are they themselves, their refusal to acknowledge the potential afforded to them by the current system, or their inherent inadequacy. This is not to say most conservatives are racists, to be sure; by inadequacy, I refer not to a focus on skin color, ethnicity, or some other superficial marker, but rather a weakness or meekness of the spirit. There can only be so many John Galts in the world.

This line of reasoning is the basis for Candace Owens’ TPUSA talk, and it seems to be one of Kanye’s new obsessions as he continues to stride the world, ridden by survivorship bias and an utter incapability to keep in tune with the issues of those outside his bubble of stardom and pretentious pseudo-artistry. Harsh words, yes, but ones that ring true once one delves deeper into the incessant stream of consciousness that Kanye has unveiled to the world through his newly reactivated Twitter account.

Every day West spits out whole torrents of bite-sized thoughts that can only be described as a mile wide and an inch deep, superficial bits of pop philosophy masked to appear as some great revelation regarding the state of modern self-censorhip and thought policing, with some nonsensical elements of spirituality thrown in for good measure.

“The more people contribute to real time global consciousness the faster we evolve” sounds like an incredibly dumbed down reading of Hegelian dialectics, except delivered in a manner that is, paradoxically, even more impenetrable than the German philosopher’s ideas in Phenomenology of the Spirit, as Kanye fails to provide even the slightest bit of context behind this word salad of mid-life angst. This is preceded by West basically advising his fans to “break out of the simulation” in order to get more in tune with their feelings, an idea that just about might’ve counted as original if it had been written in 1999 before the release and subsequent commercial success of The Matrix.

Of course it wouldn’t be a Kanye twitter feed if it didn’t feature some incredibly cliched quote of the sort that are perpetually misattributed and have already lost any semblance of meaning by the 1000th time they’re posted and reposted.

On and on it goes, tens of tweets that are completely devoid of meaning, pathos, of anything that could be even remotely regarded as intellectually compelling. Kanye went on a spree the other day, filming the screen of his MacBook with his phone in order to show his audience the incredibly valuable input of renowned paranoiac and snake oil salesman Scott Adams who, rather than admitting to having flip-flopped from Trump to Clinton and then back during the 2016 election campaign, came up with a not-so-elaborate story about how dangerous and life-threatening it was for him to be a Trump supporter and how he was at the ‘top of Clinton’s kill list’ after making some half-baked videos about Trump’s impressive qualities as a businessman and a captain of industry. The video that Kanye filmed and tweeted of course was concerned with some abstract notion of a collective awakening, ‘people breaking out of their mental prisons’, as Adams puts it, ushering in a new era. Typical MAGA chest thumping, once again nothing new under the sun; most people who’ve used the Internet for something other than Facebook and 9gag are aware of the delusional Trump supporters who hail the now-president as the man who will finally complete the system of German Idealism and raise the great cities of Thule and Atlantis, unveiling their splendor to the mortal world. And make no mistake, there are those who would, unlike Kanye, go very in-depth about their ridiculous notions, who will dredge up excerpts and quotes to support their theories as to the greatness of this celebrity or that politician, who will go to impressive lengths to provide some manner of justification for claims that are, in most cases rightly, seen as absurd or idiotic. As they should be. Not all opinions are valid, and some deserve nothing more than to be met with ridicule and derision.

In conclusion, let’s be honest for a quick second – this is all fucking meaningless. Kanye thrives on attention and we’re giving him just that. Every bit of controversy is simply going to make him even more confident in the legitimacy of his hyperinflated ego until the inevitable snap back to reality, which will most likely look exactly like it did last time – he’ll have a break down on stage and spend some time in a mental health facility, before returning home and commencing the next stage of the cycle that is Kanye’s insatiable desire to set himself apart while simultaneously being painfully generic in every aspect except for the one he should be focusing on but isn’t – his music.